By Juan Butten

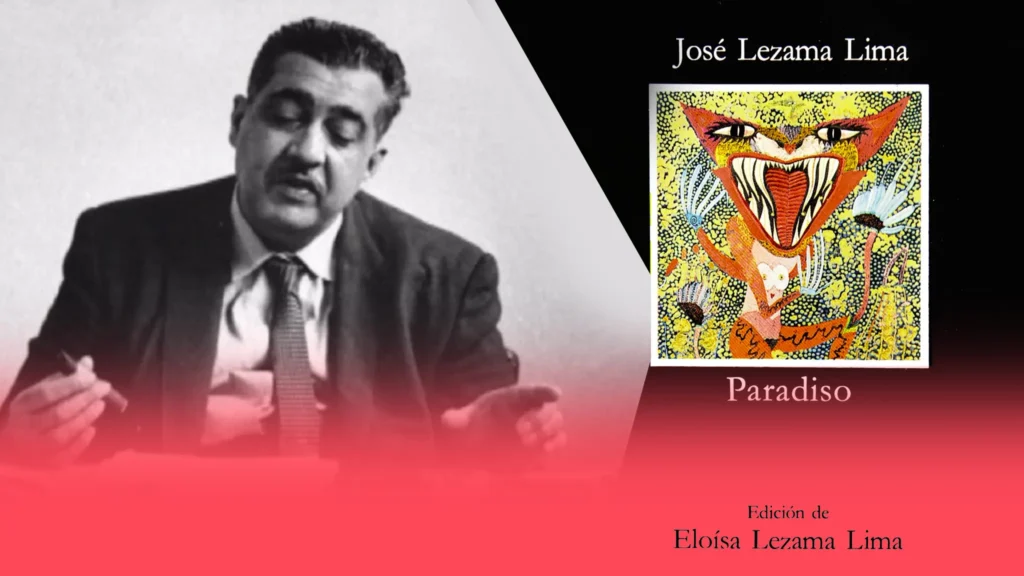

It was a Saturday in January 1998 when I found it, stacked between a tattered book by Marcalle Abreu and a typing manual, at a street stall on Arzobispo Nouel. The spine was battered; the pages, toasted and yellowed, some underlined and filled with notes in a faded blue pen. Still, it stood firm: Paradiso, by José Lezama Lima, first Cuban edition from 1966, 617 pages, part of the “Contemporáneos” collection.

I didn’t buy it on a whim or because of the author’s reputation. I bought it because a friend—one of those who read intensely and recommend passionately—had told me about one particular chapter: number eight. According to him, that single chapter justified the entire book. “You won’t understand literature the same way after that,” he said, almost like a warning. At the time, I thought he was exaggerating.

I didn’t read it right away. I left it in my workshop for months, while I witnessed the birth of my son, the sleepless nights, the hushed silence of a newly formed home. It was then, in the hormonal haze of early fatherhood, that I plunged into that universe. It took me two months to get through it. And I emerged on the other side changed.

Years later, almost by accident, I decided to reread it. But not that same copy—because that very friend borrowed it and, like many other books, never returned it. I had to buy another edition on eBay: Cátedra Letras Hispánicas, Madrid, 1993, edited by Eloísa Lezama Lima.

I rarely reread. I prefer the memory, the echo of the first reading, the way a book fixes itself in your mind like an old photograph. Because rereading, more often than not, disappoints. It’s like running into a high school ex-girlfriend: someone who once glowed with youthful beauty that time has softened. Some things, once seen again, lose their magic. And you’d rather never look at them again.

But with Paradiso, I was wrong.

Chapter eight is a beautiful trap. There, José Cemí, the young protagonist, experiences his erotic awakening—but Lezama avoids all direct narration. There are no conventional scenes, no chronological storytelling. What you get instead is a baroque liturgy, a ceremony of symbols, a mystical journey through desire.

The language doesn’t describe: it invokes. Each sentence is a drumbeat in a secret ritual. Fronesis appears, that ambiguous figure who blends beauty and wisdom, like a guide in an initiation rite. The body becomes sacred text. Eroticism, a path to knowledge.

Lezama doesn’t narrate a sex scene. He constructs a mysticism. You don’t read it—you decipher it.

As I reread, something lit up in my mind. The same murmur I felt when I read Proust for the first time. The same dizzying sensation Joyce once gave me. And I understood that Lezama belongs to that rare, luminous family of writers who don’t merely tell stories—they transform language into experience.

Proust turned time into poetic fabric. Lezama transforms it into a spiral, where myth and present spin together as if they were the same thing. Instead of madeleines, Lezama gives us words laden with myth, metaphors that burst like ripe tropical fruit.

Joyce, for his part, dismantled language to bring it closer to human thought. Lezama does the same, but in his own way: baroque, neoclassical, Caribbean. His sentences unfold like branches of a ceiba tree, full of unexpected blooms. Reading him isn’t following a plot: it’s getting lost in a labyrinth to emerge on another plane.

Lezama didn’t write from Paris or Dublin. He wrote from Havana. From an island where baroque wasn’t just a literary school—it was a way to survive excess, heat, mixture, and ritual.

In Paradiso, family history intersects with colonial history, Catholicism with syncretism, eroticism with metaphysics. This isn’t magical realism—it’s Caribbean cosmogony.

Where others narrated, Lezama created worlds.

Last night, not wanting it to end, I finished this rereading. Paradiso, a towering work of Latin American literature, does not grow old. Not because it’s eternal, but because it reinvents itself with each reading. Lezama’s language doesn’t represent: it transforms. It is body, symbol, passage.

As in Proust, as in Joyce, the novel is not a story—it’s a journey to the essential.

And I, who almost never reread, now understand that this time, I hadn’t returned to the past.

I had been born again.