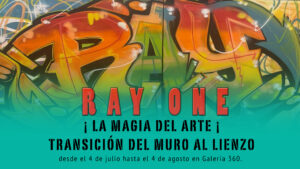

By Juan Butten

I remember Mom reading an old book. It was a book that accompanied her for several weeks throughout the house: from her bedroom to the kitchen, from the porch to the living room. I remember her reading intently on the red couch in the living room. She carried it from place to place, everywhere. To mark the pages, she used a drawing made on yellow cardstock, approximately 6 by 9 inches. I had painted it for her with my colored pencils: her name, Yolanda, formed with many small flowers, and below, in big, clumsy letters, I wrote: “I love you, Mom.”

That little drawing, which she later used as a bookmark, was a gift I made for her when I was in third grade. My Spanish teacher, Josefina, had asked us to prepare something special to celebrate Mother’s Day, and I made her that small gift with all the love in the world. Those letters… I don’t know why, but I found them so beautiful.

Many years passed before I was able to remember the name of the book and its author. I don’t usually forget things, but more than forty years had gone by since all that happened. At the time, I tried to read the book, but I never made it past the second page. I only vaguely remembered how it began. Something about a letter… something like that. But I couldn’t recall the second part of the title. I only remembered that, at the beginning, it talked about many bearded men dressed in somber colors.

Finally, on a trip to the city of Salem, Massachusetts, in early 2024, I came across a statue. When I read the name engraved at the base, I knew that was the author of the book that had accompanied Mom so much: Nathaniel Hawthorne. I discovered the exact title later, in a library in New York, where I went through each of his books until I found the right one. I recognized it as soon as I read the beginning. The book is titled The Scarlet Letter. And it begins like this: “A throng of bearded men, in sad-colored garments and gray steeple-crowned hats, intermixed with women, some wearing hoods, and others bareheaded, was assembled in front of a wooden edifice, the door of which was heavily timbered with oak, and studded with iron spikes.”

That’s when I realized: this was the book my mother had read so fervently. So, I decided to take the same journey she once did. I wondered how that book had made its way into our home, and through whom. I spoke with my older sister, and she told me that Mom had found the book on the stairs of the apartment building where we lived back then. Mom asked all the neighbors if it belonged to them, but no one claimed it. No one knew anything.

Just a month ago, after all this time, I decided I wanted to walk that same path. And it was easy to start. I began reading the book and started to discover why Mom had liked it so much. The book had been lost among many moves and hurricane seasons. But I read it. I analyzed it. And now I want to share everything I understood from it—its influence and what it awakened in me.

The Scarlet Letter, published in 1850, is Nathaniel Hawthorne’s most famous novel and one of the cornerstones of American literature. Set in a Puritan community in 17th-century New England, the novel tells the story of Hester Prynne, a woman sentenced to wear the scarlet letter “A”—for “adulteress”—embroidered on her chest as punishment for having a child out of wedlock. But beyond the surface story of social punishment, the novel delves deep into moral dilemmas, identity, religious hypocrisy, and the weight of sin in both individual and collective life.

One of the most powerful themes of the novel is the difference between visible sin, publicly punished, and hidden sin. Hester, once discovered, bears her guilt before the eyes of everyone, while her lover, Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale, endures a silent torment for not confessing his role. Through them, Hawthorne poses a fundamental question: Is it worse to commit a sin or to live while hiding it? Dimmesdale, by not revealing his guilt, is consumed physically and emotionally, while Hester, though shunned, finds an inner strength. In this way, Hawthorne suggests that the truth, no matter how painful, sets us free.

There’s also a clear critique of Puritan hypocrisy and repression. Hawthorne not only exposes the rigid morality of that society but also unmasks its double standards: a community that condemns sin in public while tolerating—or even protecting—it in private. The very society that punishes Hester reveals itself to be deeply hypocritical: moralistic in public, complicit in silence.

One of the most complex symbols in literature is the scarlet letter “A” itself. At first, it represents “adulteress,” but over time, as Hester transforms, its meaning shifts. To some, it comes to stand for “angel,” to others, “artisan” or even “admirable.” This symbolic evolution reveals how social judgment can change, how a label imposed from the outside can be redefined through dignity and resilience.

The characters are unforgettable. Hester Prynne is a strong, dignified woman who faces public shame with defiance. Over the course of the novel, she becomes almost a mystical figure—wise and compassionate. Arthur Dimmesdale is the minister loved by his community, yet broken inside. His inner turmoil is one of the earliest great psychological portraits in American literature. Roger Chillingworth, Hester’s husband, returns in secret and becomes consumed by his obsession with revenge, representing how hatred can corrupt the soul. And Pearl, Hester’s daughter, is the living symbol of sin, but also of love and truth, with an almost magical presence.

Hawthorne writes with a dense, symbolic style, rich in moral ambiguity. His narrator reflects, questions, and invites the reader to see characters from multiple perspectives. The use of symbolism is essential: the scarlet letter as a changing emblem; light and shadow as metaphors for truth and secrecy; the forest as a space of freedom in contrast to the social control of the town; the scaffold as a place of exposure, where truth is revealed, unlike the corners where sin hides.

The Scarlet Letter is not just a story about sin. It’s a profound reflection on the human condition, double standards, social repression, and the possibility of redemption. It was one of the first novels to challenge the ideal of moral purity in the United States and to tell a story from the point of view of a marginalized woman—making it a precursor to many of today’s ongoing debates. Its influence still resonates in feminist literature, in social critique, and in any work that explores the conflict between the individual and society.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, through The Scarlet Letter, offers a timeless portrait of the struggle between public judgment and personal truth. It’s a novel that unsettles, that invites reflection, and that—even though set in the 17th century—touches on universal themes. Its symbolism, emotional depth, and bold critique make it an essential work—not just of the American literary canon, but of world literature. And as I finished it, I couldn’t help but wonder if Mom was somehow watching me, smiling, as I read each and every page with wonder.