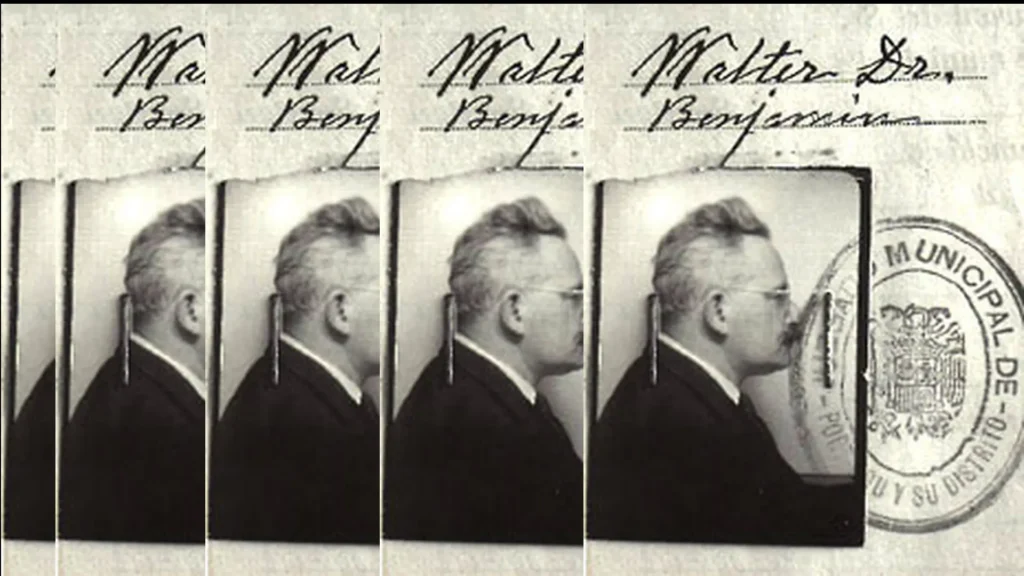

At the end of the year 2000, a friend recommended that I read Walter Benjamin, an author I had heard of but whose work I did not know in depth. His book, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility, promised to be a fascinating journey into the world of art and aesthetics. However, what initially seemed like a simple task turned into a real challenge.

At that time, Amazon did not exist, and obtaining specific books was complicated. I turned to a very famous bookstore in Santo Domingo, where I requested Benjamin’s book. To my surprise, they brought me another title by the same author: The Concept of Art Criticism in German Romanticism. I had already paid, so I could not refuse it, even though I knew it was not what I wanted.

Frustrated, I decided to ask a friend living in Spain to bring me the correct book during his visit to the island that summer. After a long wait, I finally accessed The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility and immersed myself in its pages. This is how I began to understand Benjamin’s analysis of the relationship between art, technology, and society.

In his essay, Benjamin presents a profound and provocative critique of how reproduction technologies, such as photography and cinema, transform our understanding of art and its cultural value. Published in 1936, this text remains fundamental for the study of aesthetics, cultural criticism, and art theory.

One of the most striking concepts I discovered was that of “aura.” For Benjamin, the aura is the “unique presence” that a work of art has in its original context. This aura, closely related to the authenticity and history of the work, confers an almost mystical quality. However, when a work is reproduced, its aura is diluted, transforming the aesthetic experience of the spectator.

New reproduction technologies have radically changed the way we experience art. Photography and cinema allow for the production of multiple copies, making art accessible to a much broader audience. This democratization, while positive, also entails the loss of the aura; the direct experience of a unique work is replaced by a more mass-oriented and, in many cases, superficial experience.

Benjamin argues that technical reproduction not only democratizes art but also changes its aesthetics. When works are viewed in different contexts, they can lose their original meaning. For example, a painting can acquire a new connotation when reproduced in a book or on a screen, stripping it of its original context.

Moreover, Benjamin addresses the link between art and politics. In the age of reproduction, art can become a means for social critique and political transformation. By allowing more people to access art, a space opens for debate and critical reflection on society. However, this capacity for reproduction also raises ethical questions, especially when used for propaganda purposes.

Today, Benjamin’s analysis remains relevant, especially in a world where digitalization and social media have drastically changed our way of consuming and appreciating art. The discussion around authenticity and the democratization of art resonates in the context of the production and circulation of digital art, as well as in the proliferation of images online.

In conclusion, The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility is a fundamental text that offers incisive criticism on how reproduction technologies transform our relationship with art. Through his analysis of aura, democratization, and the new aesthetics of reproduction, Benjamin invites us to reflect on the meaning and value of art in a technology-mediated society. His work not only challenges our traditional notions of art but also urges us to consider how these transformations affect our cultural experiences today.