By Laura Gil Fiallo

Member of ADCA-AICA

Head of Research at the Museum of Modern Art

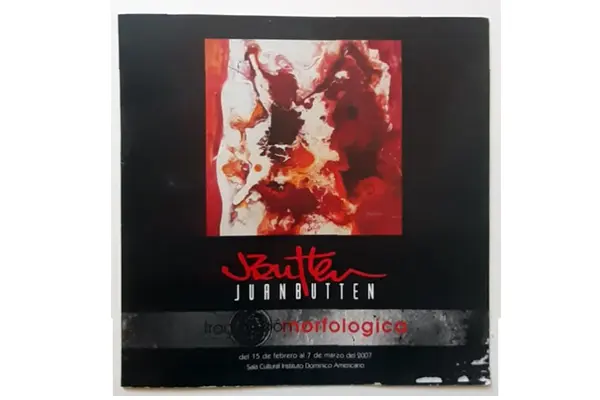

Juan Butten’s transgressions are explorations within the material itself; they are trials of the free expansion of human formalization faculties and expressions of the artist’s subjectivity and creative vigor. But above all, they are painting, and in the realm of contemporary art, this means they are the physical manifestation of an artistic choice that responds to various media, expectations, and traditions.

What characterizes Butten’s painting is the emphasis on conceptual-craft values, the immediacy of impulse transmission, and a profound and intense intimacy between the eye, the brain, and the hand.

Also, if at all, in an exaltation of the somatic and spontaneity. In this sense, informalism is, more than any other expressive option, identified with a pictorialism of painting that goes beyond the pictorialism of 19th-century photographers. It is not about imitating something else, but rather about an essentialist purity and aesthetic rigor hidden behind images that appear spontaneous but arise from a high level of aesthetic demand.

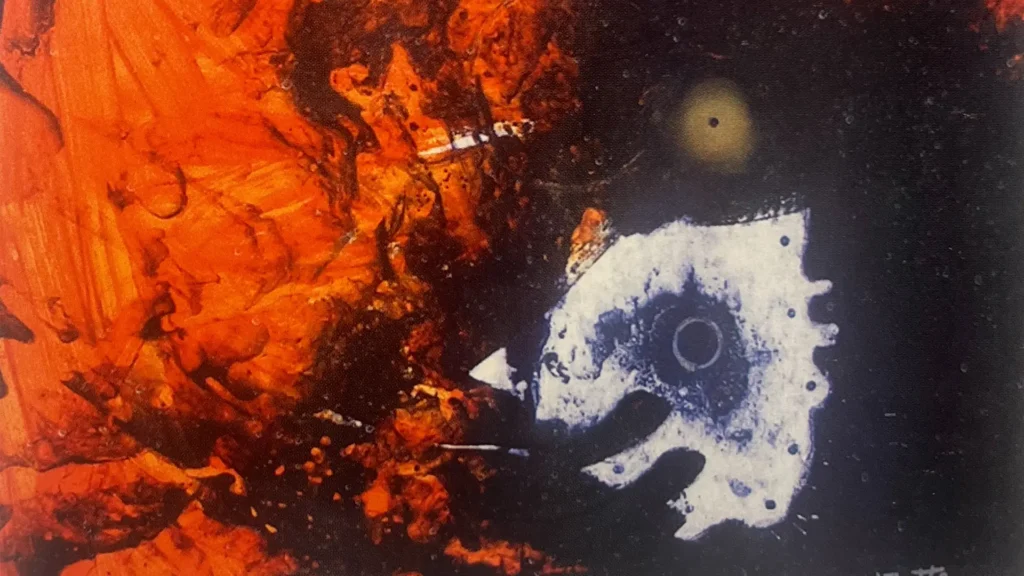

Juan Butten’s work, with its rhythmic, fluid, and spontaneous drippings, makes us think simultaneously of the rhythms of rain and the Taoist aesthetics of symmetry and immersion in nature. It is also an exaltation of matter as a complementary and opposing principle in a context we do not hesitate to consider neo-Aristotelian, in relation to form.

In these paintings, as Juan Butten once said about Spanish and Euro-American informalism (lyrical abstraction, abstract expressionism), instead of a lack of form, we discover “fluctuating forms” that replace the structured with the fluid, not the amorphous. Therefore, it is about achieving a confluence between the categories of the timeless and the temporal, in the traces and gestures of a formalization process with a static, spatial form fixed as a pictorial image.

In all cases, color becomes an incitement to the mobility of the eye, a dynamic that, while not existing in the artistic object itself, is imposed on the viewer’s vision, much like a musical score indicates a temporal sequence to the performer.

Perhaps this spatialization of time, this sequential quality, though extraordinarily free, reversible, and multifaceted, is the conceptual element of openness that the artist provides to the work, establishing a dialogue with the viewer. A dialogue that appeals to intelligence, but also, through color—bermellons, deep greens, vibrant blues, and nearly sculptural textures—touches the senses, emotions, and unconscious profoundly.

A sort of expanding magma, perfect circles with their internal energy intact but asymmetrically displaced from the centers, and drips that barely deviate in their fall, precisely guided by gravity but with small deviations that concede to principles of chance and chaos, constitute the alphabet of a language of forms that expresses, without equivocation or hesitation, the most fundamental principles of Being and everything that exists: the primordial tension between the forces of entropy and dispersion, and those generated by the ordering of the Cosmos and Life.

In conclusion, all growth and expansion represent a rupture with what is given, a form of creative destruction, like that which Indian mystics see embodied in the dance of Shiva, and which thinkers of the Western Christian tradition once expressed with this happy formula: Oh Death, who gives Life…!!!