Juan Butten

January 21, 2025

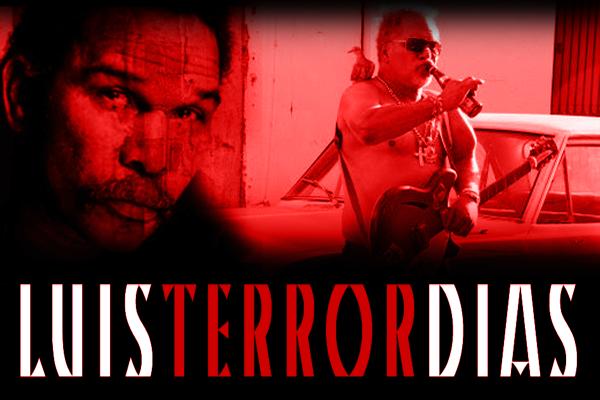

On December 8, 2009, the most widely circulated newspapers in the Dominican Republic reported the death of Luis “Terror” Días. Two days before, I had been drinking rum with him, along with Joselo, in front of a store right across from Casa de Teatro. That night, I understood why they called Luis El Terror.

In the newspapers, everyone talked about the greatness of his songs and highlighted his importance in Dominican popular art, positioning him as one of the most relevant composers of the last thirty years. The praises and accolades for his significant contributions to Dominican culture, especially in music, filled the pages of the cultural sections. They also emphasized his research into Dominican musical genres.

In several conversations I had with him, Luis shared his passion for music, his vast knowledge of figures from the Colonial Zone, and even, in a humorous way, told me about Shakira and the “jeepeta” she had sent him as a gift after using a chorus from his famous song “Baila en la calle de día, baila en la calle de noche” in Shakira’s hit “Hips Don’t Lie” without his consent.

Despite knowing Luis’s greatness, I was saddened that the newspapers, in their coverage, focused only on the most superficial aspects: his musical career. While they acknowledged his talent and the importance of his songs, they did not mention the many layers that made up his life. There was so much more to tell, from his experiences with other artists to his personal stories.

The newspapers said that Luis was born in Bonao, Dominican Republic, but the information about his childhood was vague or almost nonexistent. They talked about his outstanding musical themes, his contributions to Dominican folklore, and described his personality as a man with a “tough mouth and a soft heart,” an extraordinary human being. However, none of the papers mentioned what a night with Luis in the Colonial Zone of Santo Domingo was like, or what he was like as a person.

I knew those stories, because I had the privilege of knowing him since I was very young. Luis was a close friend of my father and my uncle, and my father told me an anecdote that I never dared to ask Luis about. In the 1970s, at the corner of Palohincado and Mercedes streets, my father saw Luis with his guitar one early morning. He asked him, “Luis, where are you going?” and Luis replied, “I’m going to Paniagua’s, in the María Auxiliadora neighborhood, near the Morgan Hospital.” Luis was going to play with one of the pioneers of bachata, but he had been drinking so much that when they reached the corner of Federico Velázquez and Albert Thomas, my father said, “Terror, we’ve arrived,” and Luis, upon getting out of the car, left his guitar behind. Laughing, my father had to go after him, honking the horn to return the guitar he had forgotten.

I had never dared to tell Luis this story, but when I finally did, he burst out laughing and said he remembered that day. He always treated me with generosity. We talked and laughed together, and we always had fun. I remember that once, he said to me, “Your dad was tough.” He referred to my dad as “El Estudiante,” a nickname given to him for the various riddles he would set up for Balaguer during his twelve years in power. This was quite paradoxical, because one of the reasons Balaguer got to know Trujillo was through my grandfather, Piro Estrella.

Personally, I don’t know any Dominican composer with more songs recorded than Luis. His ability to change genres and make them his own was unparalleled. I don’t know another artist who had that versatility.

That night, Joselo and I were walking around the Colonial Zone, visiting art exhibitions and catching up with dear friends. For some of them, living in the Colonial Zone was a dream, and that excitement was passed on to us, as if the achievement were ours. We visited a Spanish art exhibition at the Centro Cultural de España, went up to Casa de Teatro, and right across the street, we saw Luis, alone. We approached, as we always did, I ordered a bottle of rum, greeted him, and started talking to him. I was such an idiot that I blurted out, “Maestro, what about Shakira?” Smiling, he said, “Look at the gift Shaki sent me,” as he grinned. That smile was contagious to Joselo and me, as I opened the rum, poured the “trago de los muertos” and served myself half a glass, which I then passed to Joselo.

I was very glad that Luis was alone that day. He was drinking white rum straight from the bottle and humming a song that was playing in the store. The music was loud, and Luis shouted to the store owner to lower the volume. The same Terror as always, dominating the environment and giving orders as if he had some power over the owner, who obeyed and asked, “Is that okay?” Luis nodded without even looking at him, while I talked to him about my dad’s health, as he had just had heart surgery.

At that moment, someone said something to Luis about a song, and Luis yelled with a voice that seemed amplified by a sound system, “Damn it! I don’t have to be writing to any damn Cuban!” Joselo and I burst out laughing, while Luis remained very serious. That night, I understood that perhaps because of the strength of his voice, they called him El Terror.

In the blink of an eye, the place filled with people. I realized there was nothing more to say. “Goodbye” was the word on my mind, but I didn’t say it. It felt inappropriate, given how great the atmosphere was. I looked at him, hugged him, and left the store with the music blasting again. I left the empty bottle alongside the others right in front of the store, among those young people who admired Luis. Slowly, smoking, I walked away from the store and crossed the street. Joselo came with me, and we walked through Calle El Conde, crossed Palohincado Street, and arrived at 30 de Mayo Street to catch a concho (shared taxi). As we got in, I realized it was dawn.