Approaching the figure of Marcel Duchamp is to enter the world of one of the most provocative and challenging artists of the 20th century. His work, loaded with irony and questioning, has left an indelible mark on contemporary art, but what truly captured my attention were the aesthetic errors he attributed to himself and his desire to blur the boundaries of art.

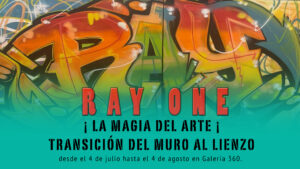

It all began with his famous “Fountain,” an inverted urinal that was exhibited in 1917. At first glance, this piece seemed simple, almost trivial. However, upon learning the story behind this everyday object, I experienced a mix of admiration and bewilderment. Duchamp presented it as a work of art, signing it with the pseudonym “R. Mutt.” The controversy it generated was overwhelming: how could such a trivial object become art? That question resonated in my mind as I tried to unravel the deeper meaning of his provocative action.

Duchamp not only challenged the aesthetic conventions of his time but also questioned the very system of art. By presenting a urinal—an object we traditionally associate with banality—he pushed us to reconsider our relationship with art and its value. Observing images of “Fountain,” I understood that its power lay in its ability to provoke reflection on context and intention. It was conceptual art, a radical questioning that did not require technical skill but rather a keen perception of what could be considered art.

As I delved deeper into his work, I encountered the notion of “readymades,” ordinary objects that Duchamp selected and transformed into art simply by his choice. This approach blurred the lines between art and everyday life, leading me to reflect on what he himself considered aesthetic errors. Duchamp, a master of humor and paradox, often joked about the seriousness of art, and I realized that his intention was not to create beauty but to open a space for dialogue and critique.

The controversy surrounding “Fountain” prompted me to ponder how art can be an act of provocation and disobedience. I was astonished by the resistance he faced, not only from critics but also from other artists who could not accept that a urinal could be considered art. This act of rebellion resonates even today, reminding us that art is a battleground of ideas and concepts.

As I continued to explore his life and work, I encountered the impact Duchamp has had on generations of later artists. His influence extends from conceptual art to pop, inspiring figures like Andy Warhol. It was clear that his questioning of the value of art had opened a path to creative freedom, allowing others to explore new possibilities. However, I always had a nagging concern: can we really call anything art? Or are there limits that, although Duchamp may have blurred, should still be respected?

Reflecting on the duality of his legacy, I realized that, on one hand, his courage to challenge conventions is admirable; on the other, his jesting about art reminds us that it is also a game. In his quest to redefine what art can be, Duchamp invites us to question our own perceptions and to be open to new interpretations. Sometimes I wonder how much his influence has helped art and how much his philosophy has harmed contemporary art.

That night, as I contemplated all I had learned, I understood that Duchamp was not only a pioneer; he was a provocateur who led us to question the very essence of art. His “Fountain,” a simple urinal, stands as a symbol of creative audacity. In a world that often seeks aesthetic perfection, his legacy reminds us that sometimes the most powerful art is that which challenges us to look beyond the obvious and to question our own beliefs. Marcel Duchamp not only transformed art; he invited us to participate in an endless dialogue about its meaning and purpose.