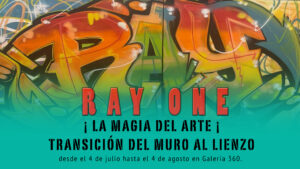

Two months have passed since this book came into my hands, thanks to a friend who brought it from Santo Domingo. De esclavos y monteros by Alexis Read spans 638 pages in a beautifully crafted paperback edition, with a cover subtly depicting the hills of San José de las Matas.

Due to my many professional commitments, I hadn’t been able to start reading it. I knew that delving into its contents would be a profound journey, as I’d been told that the book revolves around two main premises. The first suggests that those who participated in most of the battles during the independence, particularly in El Memiso and El Pinar, were ranchers and woodsmen, many of them former slaves, characters forgotten and disregarded by history. The second premise asserts that the Haitian offensive in April 1844 was halted, not at El Memiso, where fighting did indeed occur, but at El Pinar.

The first time I began reading was during one of those long train rides from Woodlawn to Bowling Green. I dove into its pages amidst the chaos of the journey, enjoying every moment. From that day on, I read it with devotion each morning, fully immersed in its world. My son often spoke to me while I read, but I couldn’t understand a word, which frustrated him. Still, I continued to lose myself in the book, initially dedicating an hour a day, but gradually reading it during every free moment.

This book, in my opinion, is a collection of several treatises in one. Chapters 2 through 7 form a mini-treatise on slavery and also discuss the Haitian domination and the struggle for independence. It also focuses on the founding of Ocoa and its role in the Battle of El Pinar, an event largely overlooked. Therefore, the wealth of information it provides should be of interest for study in our schools and universities.

One might ask why, if the book is about Ocoa, it delves into information and characters that don’t seem directly related to the subject. The reason is clear: historical events do not occur in isolation. For instance, it’s impossible to talk about the Old Maniel of Ocoa without addressing slavery in its harshest form to understand the presence of these people in the mountains of El Maniel, or the reasons behind the woodsmen from Baní venturing into the area.

Using a method that moves from the general to the particular, the author takes us through different episodes in the history of Hispaniola, including the Haitian perspective. The book provides abundant information on slavery, a phenomenon that didn’t originate in the Americas but has much older roots. Although slavery in Hispaniola was never as numerous or brutal as in Saint Domingue, the Africans uprooted from their homeland lived in precarious conditions, forced to adopt a new identity and religion. Some sought freedom by fleeing, creating sanctuaries that Read Ortiz defines as spaces of freedom, not as “dens of barbarians.”

Once slavery was abolished in our country, many Black people were assimilated as laborers in cattle ranches and other trades. This process of mestizaje shaped the current ethnic composition of the Dominican Republic, which Pedro Pérez Cabral referred to as “The Mulatto Community.” These Black people and their descendants, along with the woodsmen, were the true heroes of the wars of independence.

De esclavos y monteros

We are faced with a revisionist work that not only presents facts and figures but also questions and challenges what has traditionally been accepted as historical dogma. Was La Trinitaria a society with Masonic characteristics? What was its actual role in the events leading up to independence? Read dares to challenge these notions, presenting evidence that calls into question the official narrative.

The myth of the invincible Haitian army is debunked. Although their numbers and weaponry were superior, indiscipline reigned in their ranks. The inclusion of perspectives from Haitian and other international authors enriches the narrative and strips the work of biases that have permeated Dominican historiography.

One of the book’s greatest contributions is its vindicating nature. Read defends the Maniel as a space of freedom, where those seeking their right to be free found refuge. The book highlights the leading role of ranchers and woodsmen, rustic peasants who fought with their own tools in the battles for independence.

Read also emphasizes the importance of the battles at El Memiso and El Pinar, pointing out that two armed conflicts took place on April 13, 1844, one in each location—events downplayed in many historical accounts.

A Different Perspective on National History

Alexis Read, known for his career as a jurist, ventures into the field of history with De esclavos y monteros. This book, rich in data, is the result of exhaustive research that supports its analysis.

The work aligns with the historiographical trend known as “history from below,” which seeks to shed light on actors forgotten by traditional historiography. Read highlights the role of woodsmen, peasants, and slaves in the struggles for national independence, emphasizing how their resistance was crucial in containing Haitian troops.

Ijalba Pérez questions how history has traditionally been written by elites, overlooking many protagonists. The Dominican case is no exception, and De esclavos y monteros seeks to correct this omission.

In addition to its central theme, the book contributes to our understanding of the province of San José de Ocoa and its people. It explores the participation of enslaved and free woodsmen in the battles of 1844, reconstructing the family ties that connect many Ocoa families with these independence fighters. Read uses oral testimonies as a tool to offer a deeper, more human analysis.

The early chapters are a treatise on slavery and the slave trade, allowing the reader to better understand its functioning and implications. Read does not consider these battles marginal but fundamental to Dominican independence, and his narrative reveals how events that may seem isolated are part of a larger historical puzzle.

Although the book can at times become descriptive, this does not detract from its value. Read’s research offers a different account of national history, where the protagonists are not always the same—and that is the novelty of the work.

As Alberto Despradel notes in the preface, this book provokes reactions and seeks to rewrite history. In the end, De esclavos y monteros is an invitation to reflect on a more plural history and a broader sense of nationhood, where previously voiceless men and women are finally heard.