By Juan Butten

Ray One, the artistic name of Ramón Torres, was born in San José de las Matas, Dominican Republic. Although his given name is Ramón, almost everyone knows him as “Ray”—a nickname that originated in childhood when his mother, seeing him constantly scribbling on notebooks, schoolbooks, and any surface he could find, would exclaim: “My son, all you do is draw and draw!” And so the name stuck: Ray. That name would eventually be written on hundreds of walls—and in hundreds of hearts.

By the mid-1980s, already living in New York, Ray One began making his mark on the urban culture of East New York, Brooklyn. His signature could be seen on flyers for rap parties—those legendary “parties” organized by the Latino and African-American communities. He quickly became an “all city” artist in the graffiti world, gaining recognition as a prominent figure in the hip-hop culture of the time. His talent led him to study at the prestigious High School of Art and Design, an institution that has produced notable figures like Lee Quiñones, Calvin Klein, Marc Jacobs, and LaQuan Smith.

His work was so prolific that some thought Ray One was a collective rather than a single artist. His art has left its mark not only in New York, but also in Panama, Colombia, and most meaningfully in the Dominican Republic, where he has painted murals in nearly every province, sharing a message of faith and hope centered on Christ.

In 2010, Ray decided to return permanently to the Dominican Republic, crossing the Atlantic Ocean—more specifically, the Caribbean Sea—with his wife and children. In a personal conversation, back when I had not yet emigrated myself, I asked him why he chose to return. He answered with pride: “Here I can give my children a better education and be closer to my people.”

Back on Dominican soil, Ray found work, and almost unintentionally, returned to mural painting. A colleague invited him to take part in a community mural event in eastern Santo Domingo. At first, he declined, but his friend came to get him. When Ray saw the wall, he felt once again the joy of painting. He hasn’t stopped since.

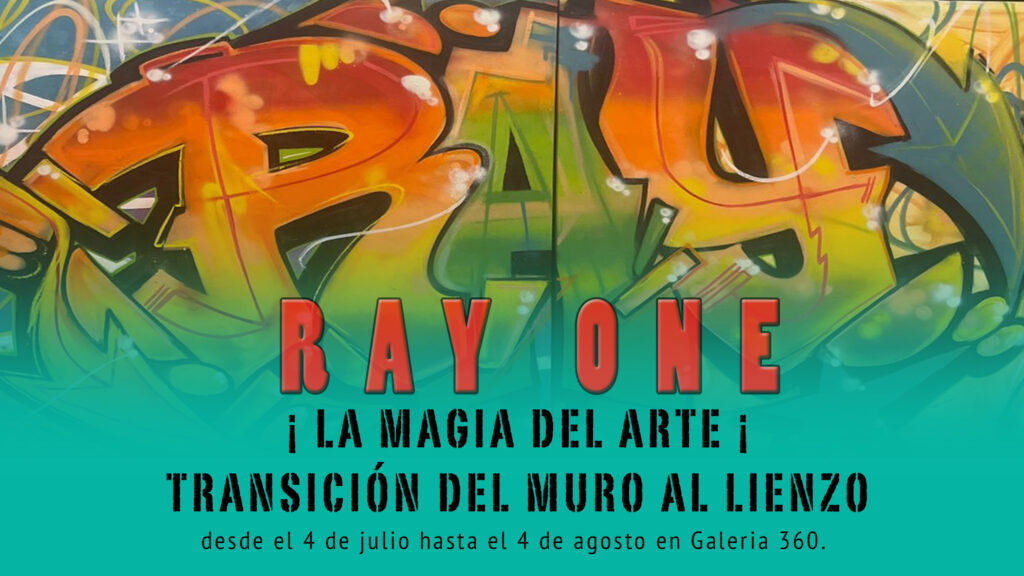

The exhibition now on view at Galería 360, located on John F. Kennedy Avenue near the Abraham Lincoln intersection, will run from July 4 through August 4. This show is a visual journey that marks Ray’s transition from wall to canvas—without losing the essence of his street origins or his commitment to truth.

The works, mostly created with spray paint and mixed media, are filled with honesty. Ray doesn’t try to impress: he paints what he sees, what he feels, what he lives. Since the beginning, he has been a visual chronicler of Dominican reality. As early as the 1990s, he created a mural titled “USA Welcomes Our Troops Back,” in protest of the deployment of Latino soldiers to war, located on Broadway near the Eastern Parkway station in Brooklyn.

In the Dominican Republic, he has painted dozens of murals with messages like “NO VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN,” winning first place in a mural competition in Boca Chica. After the killing of a couple in Villa Altagracia, Ray wrote in giant letters on a wall: “DON’T KILL ME, I’M PRAYING FOR YOU.”

In 2023, his mural of architect Leslie Rosado’s face, located on San Martín Avenue near Máximo Gómez, drew national media attention. In it, he demanded justice and transparency in the case, proving once again that his art remains a tool for protest and remembrance.

Ray One is a dedicated artist, committed to his faith, his community, and his critical view of the country. His voice has faced censorship at times, but he has stood firm. For me, knowing Ray has not only been an artistic privilege but also an invaluable human experience. He is more than an artist—he is a friend, a brother of the wall and of life.

RayOne #StreetArt #GraffitiArt #UrbanArt #ArteUrbano #ArtExhibition #DominicanArt #CaribbeanArtists #FromGraffitiToGallery #ArtAsResistance #ArteConIdentidad #DiasporaArt #Artivism #ArtAndFaith #VisualProtest #ArtThatSpeaks #MuralesQueHablan #ArtistsOnInstagram #ArteDominicano #ArteYConciencia #SprayArt #PublicArt