By Juan Butten

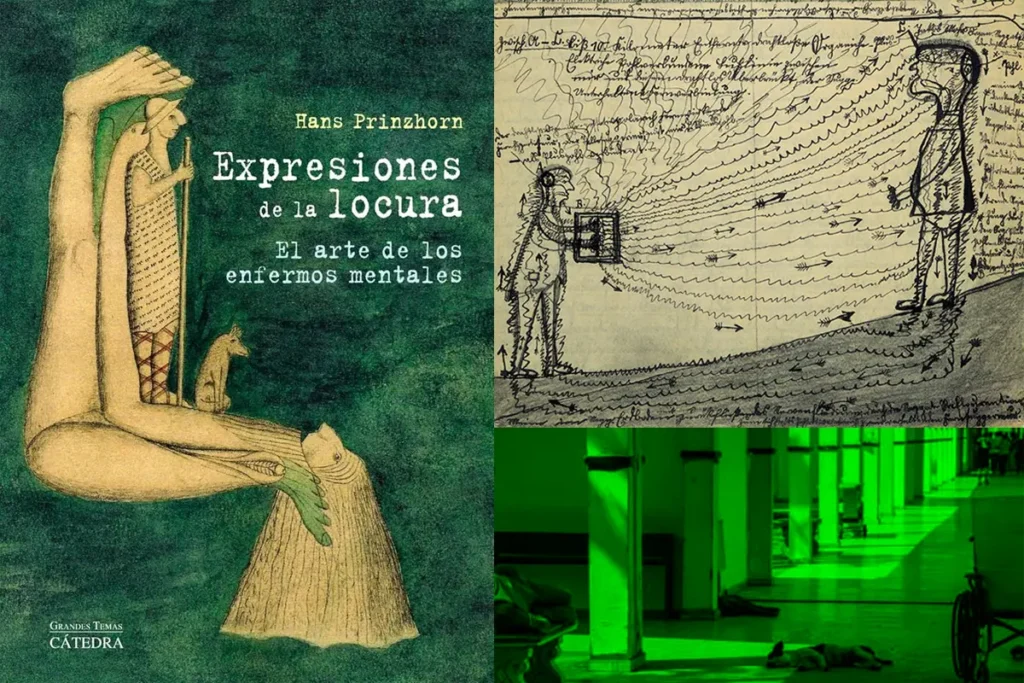

If there is a book that I have cared for and deeply appreciated, it is Expressions of Madness: The Art of the Mentally Ill by Hans Prinzhorn. This seminal work invites reflection on the intersection between madness and creativity. Every time I open it, I can’t help but recall the extraordinary drawings of our dear friend Carlos Goico, with his whimsical devils.

First published in 1922, the book has been acclaimed not only for its artistic value but also for its profound analysis of works created by individuals interned in asylums. The poet Paul Éluard described it as “the most beautiful book of images that has ever existed,” and it is easy to understand why. Prinzhorn, a psychiatrist, poet, musician, and amateur draftsman, assembled an impressive collection of works by artists considered “mad.” His enthusiasm is reflected on every page, where he establishes a dialogue between madness and art, opening a space to discuss creativity in adversity.

I often wonder how many talented artists are in psychiatric hospitals around the world, especially in developing countries, where inmates often receive inhumane treatment. How many of them could benefit from artistic exploration? What if governments and their directors sought to discover the hidden talent in these places? We should learn to value and support these voices, just as Prinzhorn did.

Since its publication, Expressions of Madness has fascinated numerous avant-garde artists, including Paul Klee, Max Ernst, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dalí. These creators found in the book a source of inspiration, considering it one of the secret springs that nourished their own work. Prinzhorn’s influence is palpable in movements such as art brut and outsider art, which celebrate art created outside aesthetic and cultural conventions.

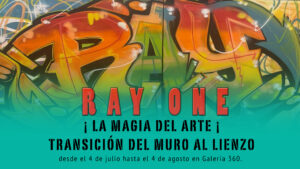

The content of the book is diverse and surprising. Prinzhorn presents stories of people who paint on toilet paper or sculpt with bread crumbs, revealing the irresistible human need for expression. These works, often seen as marginal, blur the boundaries between art and madness, suggesting that creativity can flourish even in the most challenging conditions.

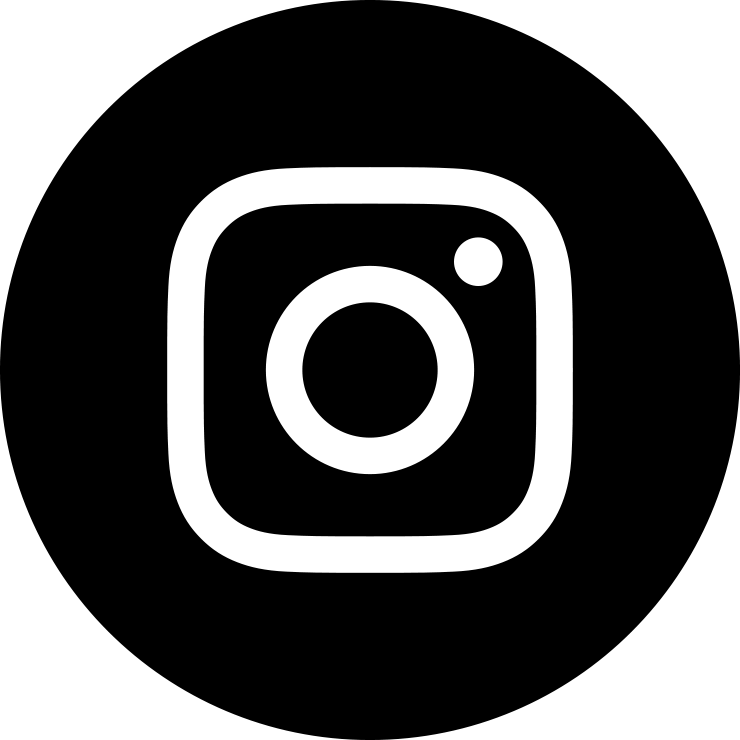

I remember that, thanks to a friend who lived near Kilometer 28, I learned about an inmate who spent nearly all her time drawing and painting. This piqued my interest, so I decided to visit her in 2008. I wanted to meet her and asked my friend to take me, bringing sketchbooks and pencils so she could continue doing what she loved. When we entered, I was devastated to see the conditions in which she and the other inmates lived; the place, more a prison than a hospital, resembled a hellish environment.

Seeing her, I felt a deep sadness. Her gaze seemed lost in nothingness, as if she didn’t belong to our reality. I handed her the pencils and notebooks, and she made a gesture of gratitude. Then she took my hand, and I felt the warmth of someone who no longer belongs to us because she exists in another frequency. I mirrored her gesture. She walked quickly and sat on the floor, starting to draw as if she had much to say and little time. My friend stepped out to make a phone call, and I remained seated, watching her enjoy every stroke, every expression on her face, smiling as she created.

On the way back, I reflected on the insensitivity of politicians in the face of such need. I sometimes wonder how they can sleep peacefully, knowing all they should do, and often choosing to ignore this harsh reality.

It is essential to create artistic policies for mentally ill patients in psychiatric hospitals in countries like the Dominican Republic. Drawing inspiration from Hans Prinzhorn’s work, it is clear that art can be a powerful tool for expression and healing for those facing mental disorders. Prinzhorn emphasized how the creations of artists deemed “mad” not only challenge aesthetic conventions but also reveal profound truths about the human experience in its darkest moments.

Establishing art programs in psychiatric hospitals can provide patients with a space to explore their creativity, communicate, and ultimately find a sense of identity and dignity. These programs not only help inmates process their emotions but can also serve as occupational therapy, promoting rehabilitation and well-being. Through artistic workshops, exhibitions, and the inclusion of patients’ voices, oppressive and dehumanizing environments can be transformed into spaces of expression and empowerment. Artistic policies should be designed with a focus on inclusion and the appreciation of the artistic talent of the inmates, fostering a dialogue between mental health and creativity that, as Prinzhorn demonstrated, is vital for the social understanding and acceptance of the realities of madness.

Through its pages, the reader witnesses the capacity of art to communicate emotions and experiences that would otherwise remain silent. Prinzhorn not only documents these expressions but also challenges the traditional perception of what constitutes “art” and who has the right to create it. His work becomes a manifesto for creative freedom, highlighting the importance of giving voice to those who have been marginalized by society.

In summary, Expressions of Madness is more than a book about art; it is a profound exploration of the human condition. Hans Prinzhorn’s work continues to resonate in contemporary artistic circles, reminding us that madness and creativity are, in some way, intrinsically connected. In a world that often fears the unknown, this book invites us to open our minds and hearts, allowing the most authentic expressions of humanity to be seen and valued.